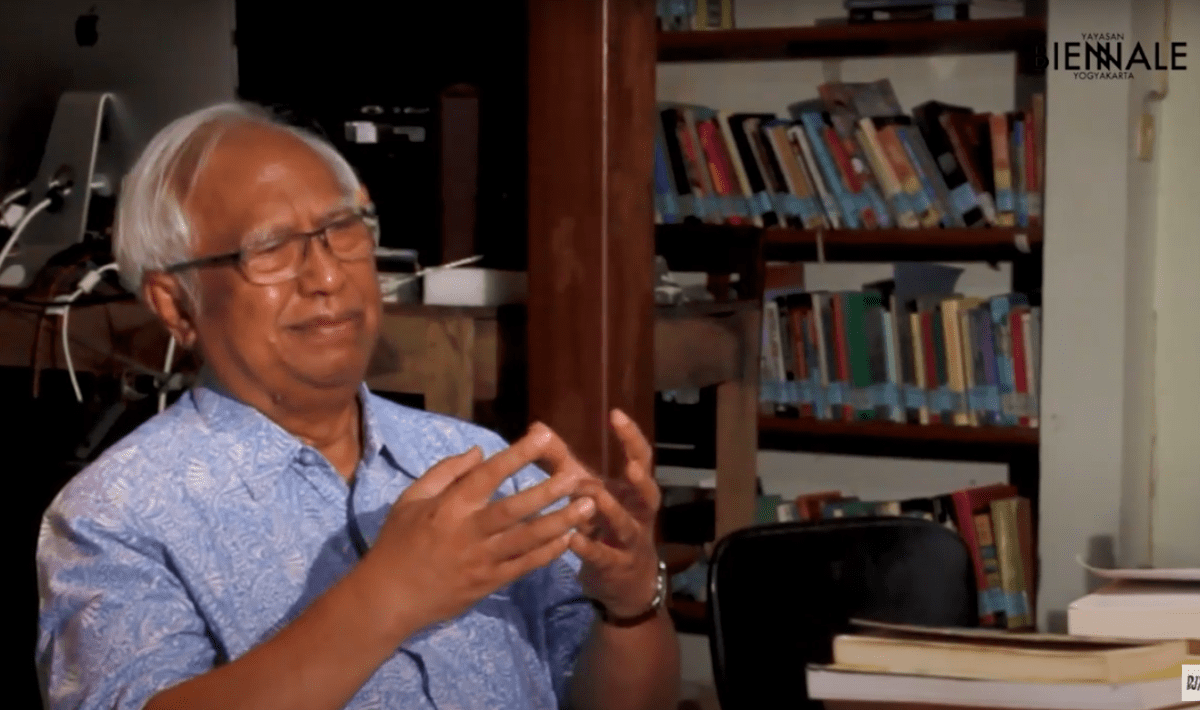

PM Laksono’s View on (Biennale Jogja) Equator: Construction of Knowledge and Distraction of Colonialism

When we consider Biennale Jogja as an alternative proposal for the geopolitical ideas in globalism, we have to re-examine many things. It is fine if Biennale takes neither the North nor the South. It means that Biennale is trying to be the center––the center of thoughts that hopefully proposes alternatives. Then, it is important to look at to what extent the assumption of giving alternatives is actually implemented. Unfortunately, I do not keep up with Biennale Jogja from time to time. Thus, it is difficult to answer the question on to what extent Biennale Jogja Equator has become a center for the movements of art, thought, culture, etc.

Discussions on the notions of global East and West are the legacy of the history of colonialism. It has been going on and on ever since. Later, the discourse was taken by the East. Indonesia frequently identifies as the Eastern nation, which is different from the West. However, the long discussions have shown that the East and the West have many things in common. In 1950s, a half century earlier than Biennale, it was widely believed that the Eastern people are irrational. But the Western are no less irrational. Otherwise, the Eastern are very rational when dealing with debts or economic exchange. They are also rational in the contexts of food cultivation and agriculture. Colonialism indeed brought along discrimination, making distinction among groups and individuals. It even applied to nature as well. The colonialist took advantage of the colonized for their own interest, such as settling their position in the global market. They made us the center of sugar producer by implementing cultuurstelsel (Cultivation System). To complement the system, they built railroads. The railroad crosses Java, passing Semarang, Bandung, Solo, and Yogyakarta. It was all for transporting the products of cultuurstelsel.

The Javanese do not have the idea of equator or the like in their mind. That idea was introduced by science or it was the result of cultural consciousness developing along with science. The world is divided. Moreover, there is not any visible mark of the equator in Java Island. The symbol of the equator that belongs to Indonesia is located in Pontianak, Kalimantan. It is presented as a monument, symbolizing the imaginary line, and functions daily as an object of tourism. Now, we’re talking about the highly diverse culture of Indonesia. Our nation even has thousands of local languages. Is it because we are on the equatorial region? Not necessarily. Either the languages or the cultures are already here in the first place, preceding our recognition of the concept of the equator line. The concept just came to our sight lately, after the society started experiencing formal education in an institution called school. Our ancient documentations of knowledge did not recognize it. As far as I know, there was not any relief about the equator sculpted on Borobudur Temple. Babad Tanah Jawa (History of the Land of Java) did not mention any single word of khatulistiwa (meaning “equator”) as well.

In my opinion, Biennale uses the word equator in order to build a relationship that defines the position of art within a different socio-political global context. The purpose is to promote solidarity among artists based in the equatorial regions. However, we have to be aware of many transformations that have been taking place in regard to the relationship between the equator and art. Take for example, the visual art. How does the equatorial landscape affect the society’s art practices? One of the answers might be related to color. In English, the word color or colour originally comes from the word calor or calorie, which means “thermal energy or heat.” Before human invented synthetic colors, natural colors came from sunlight absorbed by plants and processed in photosynthesis. Human then transferred the chlorophyll into dye materials. For example, we have “indigo” for a dye of certain color on cloth. The sun gives us color and energy. Far back then, people who were able to put color to things were considered a magician. They were even thought as people possessing spiritual power because they could capture the divine messages conveyed by the sun.

Mobilization and migration create commodities and at the same time are made possible by commodities. Keep in mind that colonialism was possible due to the presence of natural resources, a commodity produced by the nature. To the colonized, colonial discourses and the idea of commodities also bring a huge impact. The current disadvantaged regions in Indonesia have been long ignored since the colonization era. We have to be carefully aware that these regions are never colonized because the nature did not have potential for cultivation in the first place.

Colonialism also came in the form of human trafficking. They traded human back then. Human trafficking was just banned in 1869, in the second half of the 19th century. Yes, colonialism changes so many things. What makes it worse is the fact that the colonized appropriate the colonial’s way of thinking, behavior, and systems. They even internalized the identity the colonial constructed for them. The terms “East and West” are constructed as well. Moreover, we can also take a look at the concept of nationalism as a constructed thought resulted from the tension between the colonized and colonialism itself. Indonesian nationalism, for example, is not a nativism. Neither does it mean anti-Dutch or anti-foreign. Our nationalism was inspired by the history of the world nations after the World War I and II. Even the term “Indonesia” is not part of our native language. It is an appropriation of discourses developed in the global context.

And then, we imagined of being diverse but also united. The interesting thing is the fact that what united Indonesia in the first place was the colonial administration. We inherited our territories from the colonial. We recognized Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei as part of the United Kingdom. The former Dutch colonies are now our Republic of Indonesia. Thus, we are part of the global history. A more challenging question related to that fact is: how far can we—Indonesian—affect the global history? In the domain of art, we already have many Europeans studying here. In religion, we have contributed many missionaries working in Europe, Latin America, and Africa.

The world changes, so do we. Globalization is inevitable consequence of changes, encounters, and intersections. We have to question ourselves further. To what extent are we able to be productive and thus inspire the world, instead of being an object to be claimed as what happened in the past? We should be an inspiration for the world in improving humanity. Our ideological foundation, Pancasila, lately received appreciation from other nations. As a nation, we were once colonized. The people are highly diverse in terms of social and cultural circumstances. We encounter conflicts related to ethnicity, religion, and race. Nevertheless, we are able to develop our idea of living as a nation, building a state, and formulating our ideological foundation, Pancasila. It is an innovation that might possibly inspire the world. Regardless of such a powerful concept, it is the resources that in fact really matter. If the resources do not contribute anything, then the concept means nothing. The West influence their East counterpart through the distribution of products, petroleum and energy industries, technology, electricity, and so forth. All these influences are mineral-based. They dominate the market.

As far as I am concerned, either the concept of “equator” or Biennale Jogja Equator has not been fully elaborated. It seems superficial. It might be a mere expression of separating ourselves from the rest, or at least contesting the existing. If one of the imaginations is promoting solidarity among artists based in the equatorial regions, we have to set the ground. Due to our shared experiences of colonialism, we might have our common view on “the foreign” or “the other.” The actual need is to formulate a certain issue Biennale Jogja Equator is trying to address. Observing the organization of the event over time, the issue is sometimes pretty clear, while in some other times it might seem absurd. We need to examine many ideas we have been coming up with, and single out some that are going to be discussed further. We can take for example a phenomenon of equatorial region, which is the presence of termites. They always come near any lights. But even if the termites are gone, the light is still lit. Employing this kind of metaphor in our imagination of art might be quite interesting.